Any PR, marketing or ad pro can learn to be creative. Here’s how.

Summary:

Anyone can learn to become more creative by following a straightforward process over time.

With practice, the areas of your brain responsible for creativity will strengthen.

This process can be applied to either creative hobbies, or professional creative pursuits.

We can teach creativity to communications, marketing and advertising professionals. Creativity simply comes from your brain more rapidly and efficiently connecting thoughts, which we can train just like math, science and music.

I’ve developed a process to develop creative thinking for communications, marketing and advertising professionals that (appropriately) borrows from and builds on decades of thinking on the creative process.

I wrote this guide focused on PR, marketing and advertising professionals and students who want to learn the fundamentals of becoming a better creative. But hopefully, anyone who enjoys creative pursuits will find something useful from this guide!

***

Steve Jobs famously adapted a quote from Picasso (though it may have actually been said by TS Elliot): “good artists copy, great artists steal”. Jobs, knowingly or not, derived many of his thoughts about creativity and ideation from classic works on the topic. By “steal,” he, Picasso and many others suggest not stopping at simply copy-and-pasting someone else’s work, but to make it your own by building on it.

James Clear defines creativity in a way that Jobs may have liked:

The creative process is the act of making new connections between old ideas or recognizing relationships between concepts. Creative thinking is not about generating something new from a blank slate, but rather about taking what is already present and combining those bits and pieces in a way that has not been done previously.

And in fact, if you analyze what is happening in your brain during the creative process, Clear’s point about “combining old bits” comes to life. In The Runaway Species: How Human Creativity Remakes the World, Stanford neuroscientist David Eagleman and Rice University professor Anthony Brandt explain the three main components of what your brain does to information it receives: it bends ideas to see them differently (like a Frank Gehry building), it blends two ideas together for form a new one (like a DJ Cummerbund mashup), or it breaks ideas apart into smaller fragments (like a Picasso painting).

Gehry, DJ Cummerbund, and Picasso are all considered incredibly creative artists. And while each physically or digitally started with a “blank canvas,” Gehry didn’t invent buildings, nor did Cummerbund invent music, nor did Picasso invent painting. They bent, blended and broke examples in their brains, which resulted in magical outputs onto that canvas.

These magical outputs met the threshold for creativity defined by Anna Abraham in The Neuroscience of Creativity: 1) the ideas were original, unusual or novel in some way, and 2) the ideas were satisfying, appropriate or suited to the context in question.

I cite all this to offer an approachable definition for creativity where many people could find success: creativity is recognizing relationships between things, and relaying those relationships by producing something satisfying and original.

You could apply this definition to music, dance, writing, really anything; most of those fields have existed for hundreds of years, and yet, creative people continue to recognize and express new relationships in each field (and many others).

Diving into the methodologies of how the most creative musicians, dancers, writers, etc., made their works, usually boils down to, I have thought about, consumed, and practiced my craft for a long time. That’s inspiring, but we can better explain that process for others to learn from.

More than 80 years ago, an advertising executive named James Webb Young tried this. Frustrated by a lack of accessible, specific literature on creativity, he published a 38-page guide called A Technique for Producing Ideas, which outlined a simple process to develop creative ideas. Future versions of his book expanded on his original thinking, but many of Young’s thoughts still hold up today.

Keeping with my theme, I’ve developed a teachable creative process that builds on many of Webb’s original ideas and blends them with other research and my own experience.

1. Consume a healthy content consumption diet.

This is the “input” phase of your creative journey. Your ability to generate original, satisfying ideas – even if they are simply better versions of what happened before – depends directly on the ideas you receive.

“Garbage In Garbage Out” applies. It’s very rare that great works come from people who aren’t also consuming high-quality content in that field.

I find many materials that talk plenty about the importance of “quality” content, but don’t do a good job defining what that means. So, I created the following definition: a quality content diet blends variety, sourcing and depth.

Let’s dispel a myth about variety. No, it’s not bad that you watch superhero movies, or that you spend an hour scrolling through TikTok, or that you play video games. It’s fine. Everyone needs to engage in their interests (and let their minds wander). But that can’t be all you do.

Similarly, reading blogs about your company or industry shouldn’t be all you do, either. Do some of those activities.

Also dip into topics that speak to your passions, topics that make you curious, and content styles outside your norm. When was the last time you read a poem? Or went to an art gallery? Or consumed content about a topic way outside your typical interests?

Sourcing has taken on added importance in the last decade with the return of misinformation. As content consumers, I could tell you all the moral reasons to not spread misinformation, and to trust certain sources over others.

But as content marketers, the path forward is clear. Nearly every meaningful content distribution channel is trending toward a future where unoriginal, anti-fact, and shoddy content performs worse than alternatives.

Your ability to create this high-quality content that distributors prefer starts with consuming high-quality content. Yes, engage with people in your circle you trust. Yes, consume what’s working on social networks and streaming platforms. But mix that with consuming content from trustworthy people in your institutions, like professors, and eventually, subject-matter experts in your companies. Experts, journalists, academics and researchers also produce detailed, well-researched information that has never been easier to find.

A healthy blend of sourcing and variety leads to a variance of the depth of content. We all consume plenty of short social content. And that’s fine. Many of us also regularly read news and opinion articles on websites. That’s great. I hope many of you watch movies, documentaries and listen to podcasts.

But blend with that more detailed works, like long articles and books. Better yet, talk to people and go to places (safely) that can give you added depth and insight.

MOST OF ALL, never blindly consume. Always be thinking. Analyze, process, and engage with the content. Do you agree? Why or why not? How does this compare or contrast with other content you’ve consumed? Do they offer different perspectives? Which one do you agree with, and why?

I believe that anyone who works in creative pursuits should always maintain a healthy content consumption diet. In my opinion, the best creatives make a healthy content consumption diet part of their daily lifestyle.

Living with a healthy content diet makes preparing for a creative problem that much easier. When you receive a brief, a client ask, etc., create a miniaturized, healthy content diet tailored to the brief. This will familiarize yourself with the topic, the ask, and (crucially) what creative works/doesn’t work in that space.

2. Work the content over in your mind.

This is, in my opinion, the most important step when it comes to training people to become more creative. By performing this step over time, we train, strengthen, and accelerate the executive functions of our prefrontal cortex and improve its ability to find relationships and solve problems.

Working the problem over can happen in many ways:

Reflect on it in a journal/scrapbook

Talk to other people about it

Have a brainstorm

Try creating something, not worrying about its quality or final form

This step is best completed in intense, non-distracted chunks of time; put headphones on, silence your phone, close the door, etc. We want to direct the entirety of our conscious mind’s power toward chewing over information and solving problems, and distractions, gadgets and hallway conversations sap precious braincells.

It’s at this point where I find most budding creatives get stuck, and where most literature on “working the problem” stops. So much of the content about ideation tackles it at a philosophical level. But I want to literally explain what we do with this intense, non-distracted time.

I made the following list of sample prompts that could be used during this phase of the creative process, to analyze information from every angle, search out relationships, identify opportunities, etc.:

What creative problem was the author trying to solve?

What was the highest-level message/takeaway of this content?

What surprised you about this content? Why?

Did this content change your opinion about anything? Did it reinforce an opinion you already had? What does this say about that particular opinion of yours?

How did this content make you feel? Why might that have happened? How does this content relate to an experience, a memory or an emotion of yours?

If this content didn’t make you feel anything, can you hypothesize what emotions the creator wanted you to feel? Can you explore inward to investigate why the content didn’t evoke that emotion in you? What needed to happen for that emotion to be invoked?

Can you draw any lessons from this content?

Put yourself in the shoes of the characters in the content. Do you understand their thought process? Do you have compassion for their point of view? Do you agree with their choices? Why or why not, to all of these?

Apply those lessons to past versions of yourself. What would you have done differently, now that you have consumed this content?

Do these lessons apply to other people or issues in the world around you? How so?

What about this content do you not understand?

Does this content relate to a problem, a challenge, or a question you currently face? What is that relationship?

Does this content make you curious about any other topic, related or otherwise? How might you act on that curiosity?

What roadblocks stand in your way to further exploring that curiosity / that lesson / that relationship? How could you remove, lessen, or overcome these obstacles?

The best creatives constantly work content over in their mind. They keep a journal, scrapbook, or a hobby where they can freely create without worrying about quality of the final form (a “creative outlet”). Don’t wait to start practicing processing content until you have a creative problem to solve.

Like Step 1, regularly working over content in your mind makes you that much more proficient when you need to concept for client briefs.

3. Summarize your findings, and instruct your mind to find a solution

After your intense digestion period, don’t just put it down and walk away. We’re going to create a pointed summary of what we’ve learned to this point.

But it’s not simply a recap of the work you did. We’re actually going to instruct our subconscious mind to help us find, in step 4, solutions to our problems.

What? Looking ahead, step 4 involves the subconscious mind, a supercomputer that can solve many problems so long as the problems are properly stated. (another favorite Steve Jobs-ism.)

This summary does not need to be long. It should cover:

Define the creative problem you seek to solve. What’s the ask? What are you creating for? Ideally, you should know some or all of these details:

Who needs this problem solved? How quickly?

Who is the target audience that this organization is trying to reach?

What does the organization want the target audience to think, feel and do? Why?

What reasons would the target audience not think, feel and do those outcomes today?

What proposed solution is the organization offering?

Why would the target audience benefit from this solution?

What barriers exist between the solution and the target audience?

Outline the steps you took in your input and digestion period

Summarize the most relevant or important points from this period

Lay out the problems, obstacles and gaps not yet solved. State them clearly, and accurately. This is important.

And then…

4. Walk away from the problem

We walk away.

Many of us have had incredible ideas pop up when doing activities unrelated to our creative problem, like taking a walk, folding laundry, or, the worst of all, while falling asleep.

This is the subconscious mind at work. Your subconscious mind works on problems even when your conscious mind does not.

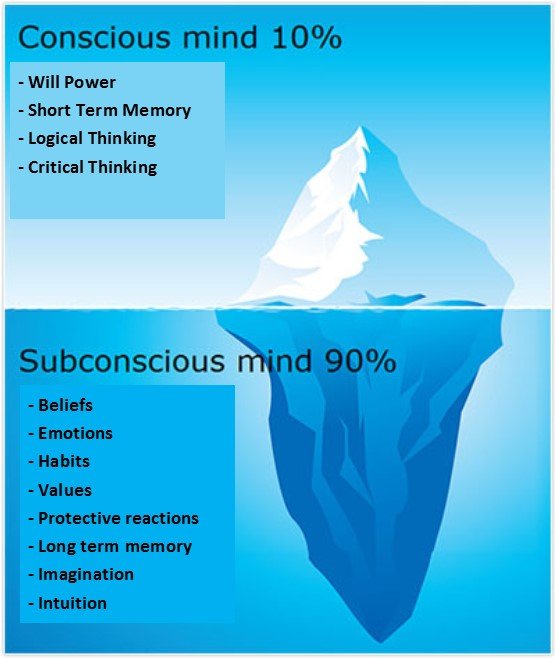

How? Remember how important it was to remove all our distractions in step 2? It’s so important because our conscious mind only harnesses about 10% of our brain's processing power, at most. And since the conscious mind serves as the primary input mechanism for your whole brain, that 10% has a lot of responsibilities.

Original creator of this image can be found at: http://www.thefatherofsuccess.com/what-role-does-of-the-subconscious-mind-play-in-determining-success/

First, it needs to keep you alive. Your conscious mind makes sure you breathe. It also scans your surroundings and allows quick reactions to your environment. If you’re in the middle writing a sweet blog post and a velociraptor appears, your conscious mind fires up your fight-or-flight response (in the reptilian/triune part of the brain) to, hopefully, run away. If the entire 10% of your conscious mind was directed on that blog post, you’d be raptor food.

Second, your conscious mind houses all of your logical and critical thinking. If you feel hungry, your conscious mind tells you to go eat. If a street light is red, your conscious mind tells you to stop the car. If you are writing that sweet blog post and your laptop is about to run out of battery, your conscious mind tells you to plug it in.

So, even when you shut out all distractions, your conscious mind inherently has other things to worry about that divert from your work.

The other 90% of your brain’s processing power comes from the subconscious. The subconscious mind is like a supercomputer, with massive memory banks and several times processing power of your conscious mind. It's CONSTANTLY working, hence the ideas that pop up seemingly at random.

Your subconscious mind houses many of the functions of the brain that aren’t mission-critical to keeping you alive: your beliefs, emotions, habits, values, long-term memory, and – importantly for us – intuition and your imagination. Also important: your subconscious mind does not spend its resources on logic or rules; that’s all the conscious mind.

So let’s review: a supercomputer not bound by the rules or logic of your day-to-day life? Infinite processing power and no rules? No wonder the subconscious produces so many awesome ideas.

But this lack of logic and critical thinking also explains why it’s so important to clearly and accurately define the problem at the end of step 3. Without giving this supercomputer parameters within which to solve, it may produce amazing information that has nothing to do with our problem.

The outputs of the subconscious mind depend on the quality and depth of its inputs. Remember, creativity comes down to finding relationships between bits of information. To this point, every step has focused on bringing in as many high-quality points of information as possible.

You raise the possibility of finding relationships with more information points. It’s a matter of factorials, the mathematical equation to calculate possible combinations. If you have three bits of information, you provide your brain a potential six combinations (3 x 2 x 1, or, 3! = 6).

Provide your brain with 10 bits of information (10 factorial, or stated mathematically, 10!) and you jump to a possible 3 million possible combinations. Your objective in steps 1 through 3 is to raise that factorial number as high as possible, so the mind (conscious and subconscious) can churn through centillions of potential information combinations.

Research has found that creatives who conduct this “walk away” step – classically, called “incubation” –are 39 percent more likely to find connections among distantly related ideas. It also takes time. Hopefully, you are beginning to understand the challenges of coming up with great ideas on tight timelines.

5. Return to the problem (via “eureka” or purposefully)

After you give the subconscious mind some time to work on problems, amazing things happen.

Sometimes, the incubation period surfaces an amazing answer out of the blue. This is commonly called the “eureka moment,” and many classic creative processes – including Young’s original – largely stop there.

This assumes creatives have infinite time to allow their subconscious to deliver an idea. That’s rarely the case. Sometimes, you simply need to return to the problem a few days later, eureka or not.

Worry not. Just because you didn’t have a “eureka moment” doesn’t mean your subconscious hasn’t been hard at work.

After a few days, return to the problem by revisiting your digestion materials from step 2 and your summary from step 3.

In all likelihood, you’ll arrive at ideas, thoughts, solutions, etc., that days ago you could not. These are the outcomes from your subconscious mind’s time at work.

Not all ideas arrive as a fully-baked, totally ready-for-prime-time idea. Usually, ideas arrive as fragments that need processing, development time, ideation, etc. That’s okay! You can always return to step 2 to chew on this new phase of the problem. This is why so many agency creative teams will regroup after a few days away chewing on a creative brief.

***

Repeating this process over time strengthens your prefrontal cortex by helping neurons connect more quickly, improving the quality of what you create in steps 2 and 3. Getting better at steps 2 and 3 vastly improves what happens in step 4, which exponentially improves your chances of quality outcomes in step 5.

If you repeat this, over time, your creative brain will develop!

Broad advice:

It all starts with a quality content consumption diet. Quality = a blend of sourcing, variety and depth.

Really push yourself to stay focused and be exhaustive in step 2. Examine the problem, in detail, from every angle. Create new prompts, or new methods to work problems over.

Don’t skip over the summary.

The creative process takes time. Start working against problems early, ideally well ahead of your deadline.